🇸🇬🇲🇾🇹🇼🇯🇵 Travel Logs v2025.04: 8 cities

Table of Contents

Originally written in Chinese and translated into English using Sonnet 4.5

🇸🇬 Singapore

I took a direct 16-hour flight from Vancouver to Singapore—the world’s second-longest commercial route, beaten only by the 18-hour New York-Singapore leg. I thought it would be brutal, but after popping two melatonin pills, I slept through about 12 hours of it.

Landing at 7 AM, I took the metro from the airport into the city to my hostel. By 8 AM, the trains were already packed with foreign workers heading into the city—mostly exhausted South Asian men in worn clothing, a stark contrast to the local white-collar commuters. Of course, Singapore’s inequality toward foreign workers is hardly breaking news.

I’d planned to stay three days and two nights in Singapore—mainly to allow time for jet lag recovery. Surprisingly, I adjusted on the first day and even managed to walk over 20,000 steps, which genuinely caught me off guard.

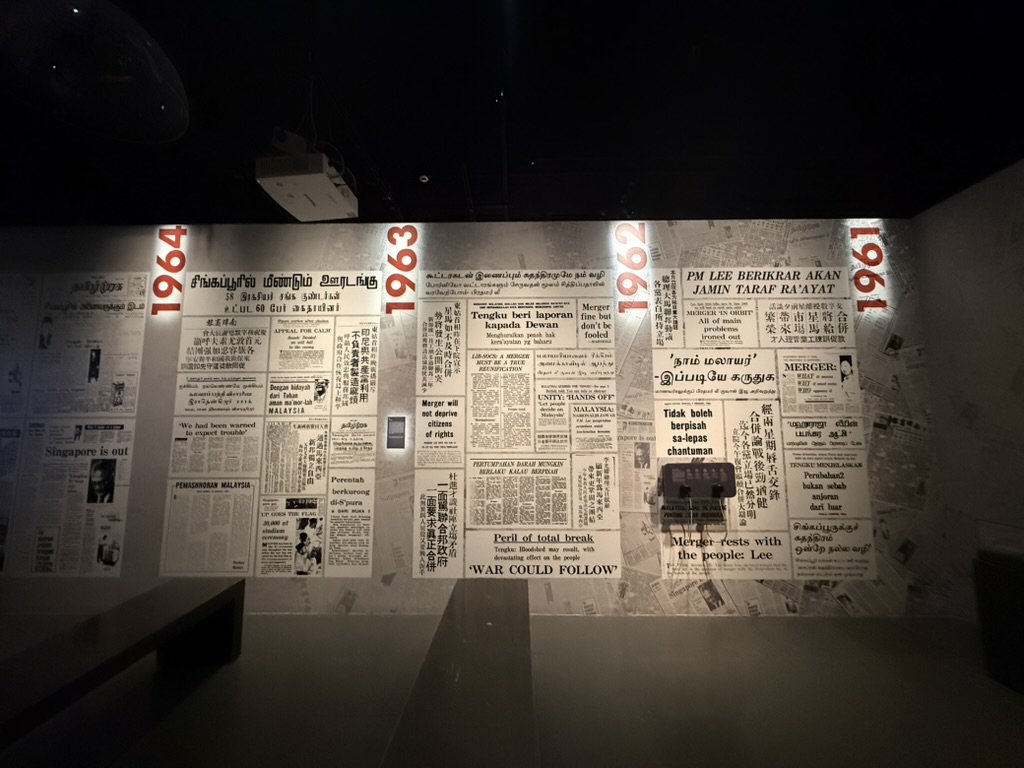

Singapore’s museums are incredibly interactive and educational, with compelling narrative design. The exhibits on British and Japanese rule, as well as the challenges and struggles during independence, were particularly detailed. I also learned a great deal about Southeast Asian history more broadly.

Beyond the National Museum, I visited the Former Ford Factory —a fairly obscure spot in the western part of the island.

This was where British forces surrendered to the Japanese in February 1941. It’s now been converted into an exhibition space with incredibly detailed coverage of Singapore’s modern history—from development under British colonial rule, through Japanese occupation, to post-war recovery and independence.

On my second day, I lucked into an open house at The Istana, the presidential palace—they only open two or three times a year. I got to meet President Tharman Shanmugaratnam and the First Lady, spending about half an hour touring and interacting with them.

Tharman won the presidency with the highest popular vote in Singapore’s history (70.4%), with strong support across all ethnic groups. The First Lady is of mixed Chinese-Japanese heritage, making them genuine representatives of “cross-ethnic unity.”

The food in Singapore felt pretty mediocre value-wise overall. Several Hainanese chicken rice meals didn’t even measure up to what I’ve had at a Singaporean restaurant back in Vancouver… Non-Singaporean cuisine was generally expensive and underwhelming.

🇲🇾 Kuala Lumpur

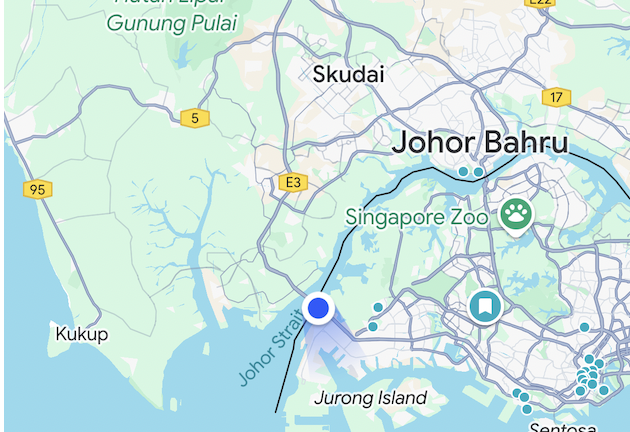

Given the short distance between Singapore and Kuala Lumpur, I decided to take a coach bus across the border. Apart from childhood trips with my parents on tour buses, I’d never actually taken an intercity coach—it was quite a novel experience.

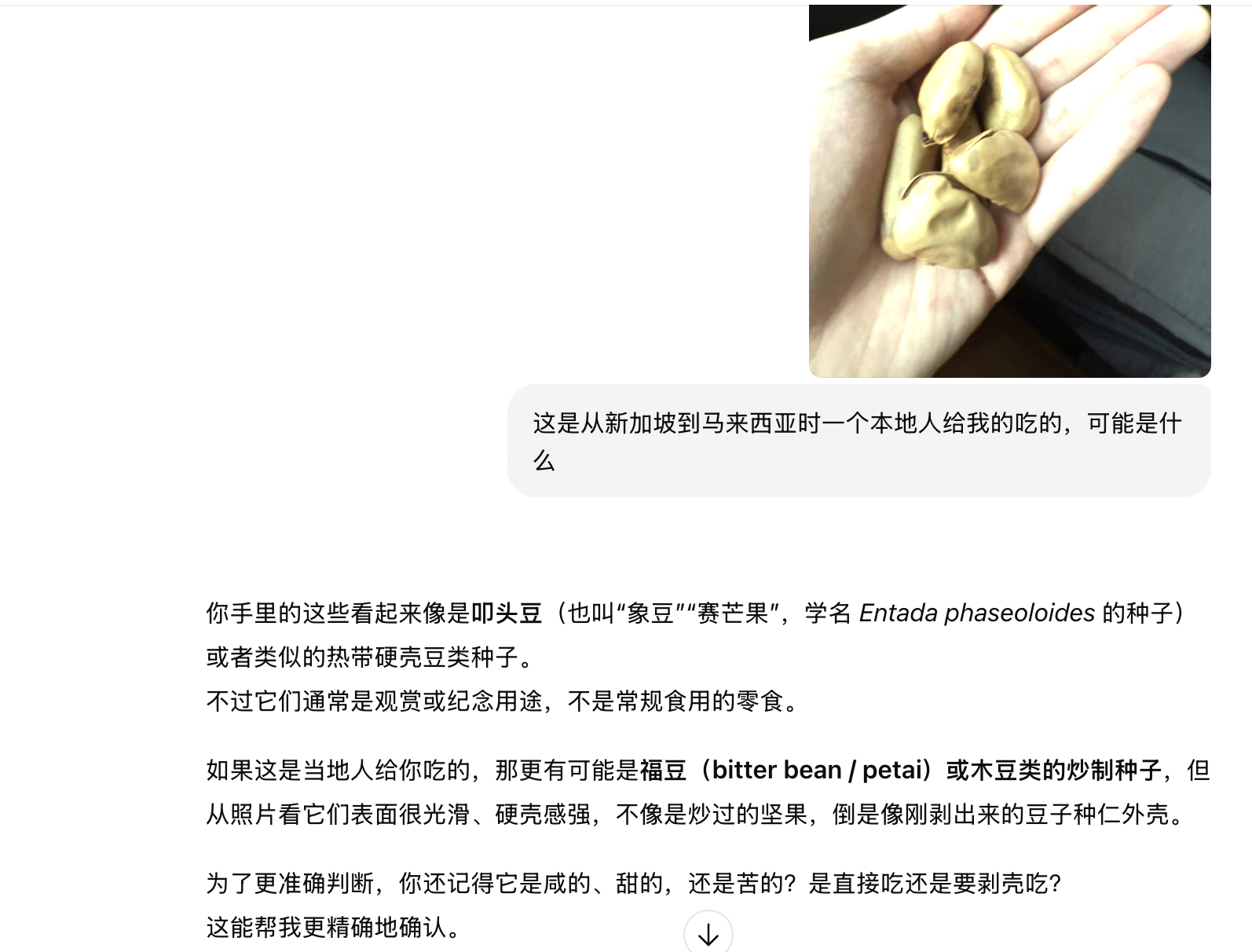

I helped an elderly Malaysian man open his packed lunch on board, and he shared some mysterious beans with me. They tasted bitter and astringent, though he seemed to relish them. I eventually gave them back.

Security was refreshingly casual and smooth. When I asked if my film could be hand-checked, customs just waved me through. I suppose they mostly deal with tourists coming from Singapore anyway.

Kuala Lumpur’s public transit system is incredibly complex. Payment methods are stuck in the traditional card-swipe era (buses don’t even accept cash), and different lines require different transit cards. It’s not just unfriendly to tourists—locals often look just as confused.

Ride-hailing is genuinely cheap, though. While KL is designed as a car-centric city, traffic is perpetually congested. Multiple times I spent half an hour waiting for a ride that took only 10 minutes. Local drivers told me it’s always been this way. Oh well.

The contrast between Kuala Lumpur and Singapore is fascinating. Both cities bristle with skyscrapers, but if Singapore is clean, orderly, and sterile in its precision, Kuala Lumpur is vibrant, full of street life, yet somewhat chaotic and wild.

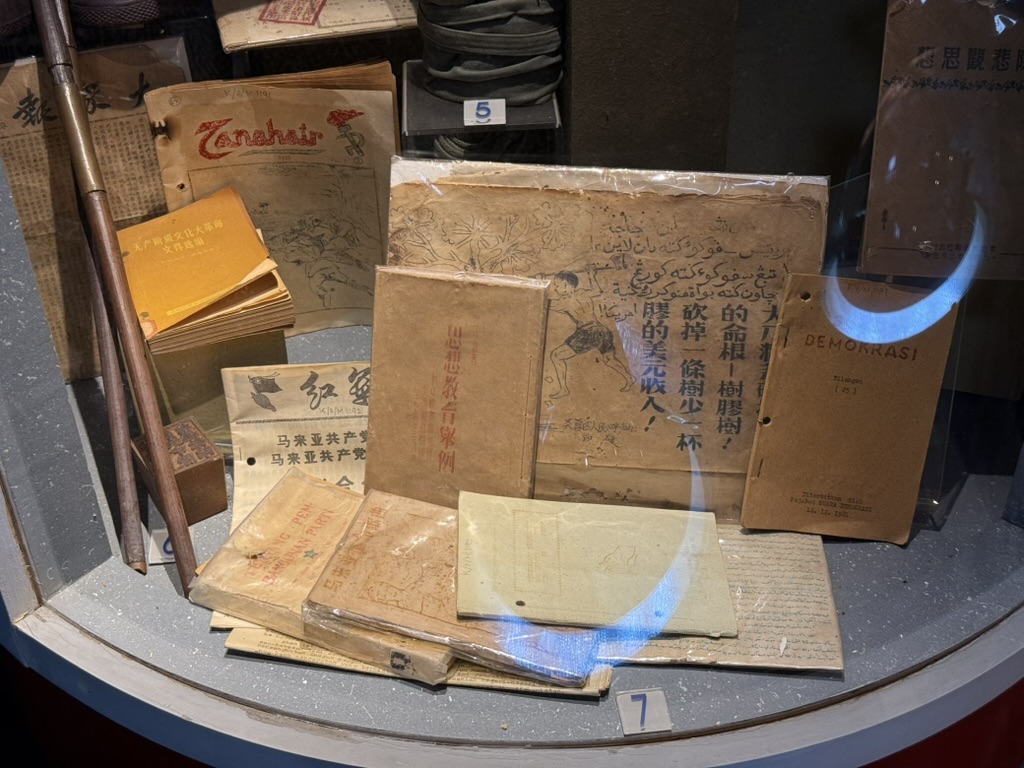

I visited the relatively obscure Royal Malaysian Police Museum , which displayed weapons and equipment seized from opposition forces and terrorists (the Malayan Communist Party). Museums really are echo chambers of national ideology.

At the museum, I met a middle-aged Saudi worker on a layover and a recent graduate heading to work in Japan—an elite backpacker type. We ended up touring together for the day. The latter’s passion and knowledge of history was absolutely jaw-dropping. One of his travel goals is to visit every Sun Yat-sen memorial hall in the world (turns out Sun’s influence was far greater than high school history textbooks suggest). I learned a lot about Taiwan from him.

Perhaps from lack of exercise, my left leg started bothering me after two days of walking in Singapore. It didn’t improve during my first two days in KL despite plenty of walking. So I ended up staying near my accommodation (in a fairly central area), focusing on browsing nearby bookstores and reading books and commentaries on the country’s politics and history.

During this time, I learned about an unavoidable event in Malaysian history—the May 13, 1969 ethnic riots. Even before that, Malaysia was controlled by ethnic Malays, and the constitution (Article 153) already enshrined Malay privileges in exchange for granting citizenship to Chinese and Indian communities.

The causes of the conflict remain disputed. The official government narrative tends to frame it as conflict with the Malayan Communist Party, framing the response as necessary for national stability. The Royal Police Museum especially emphasizes this angle, showcasing items seized from the communists during the emergency period. The prevailing civilian view, however, attributes it to long-standing economic inequality between ethnic groups, with accumulated tensions finally boiling over. Afterward, the government introduced the “New Economic Policy” to further support Malays and other disadvantaged groups.

Apparently, this topic is considered a red line by Malaysian authorities. Given the complex ethnic narratives and historical transformations involved, the general approach has been to suppress discussion. It’s mainly brought up during political campaigns as a tool for warning and intimidation. KL has few related sites or memorials.

However, I did find numerous Chinese-language books about May 13 in bookstores—memoirs from survivors, analyses of Malaysian policy issues. There didn’t seem to be extremely severe censorship. Of course, this might relate to Malaysia’s current political instability and frequent party turnover.

This made me reflect on how such historical ethnic issues often represent structural contradictions that are difficult to resolve. The constitutional clause guaranteeing “Malay priority” inevitably affects other ethnicities’ sense of belonging, yet without such affirmative policies, the economic gap between groups might widen further, triggering greater social unrest.

🇹🇼 Taipei, Tainan & Kaohsiung

Taiwan was the centerpiece of my trip. I planned to visit Taipei and Tainan. Originally, I wanted to fly from KL to Tainan and then head north, but apparently only Taipei’s Taoyuan Airport handles international flights, so I had to fly to Taipei first and then double back.

Taipei reminds me a lot of Beijing. It has both modern high-rises and architecture rich in Chinese cultural elements—a blend of tradition and modernity.

Taipei only became a political center in the late 19th century, underwent modern urban infrastructure development during Japanese colonial rule, and experienced massive expansion after 1949 following WWII. So while its history isn’t particularly long, its modern and contemporary development is quite story-rich—the entire city is essentially a museum of over a century of East Asian modern history.

Tainan is quite the opposite. As Taiwan’s first urban settlement, detailed records date back to the 15th century. It went through Dutch, Qing, and Japanese rule, preserving architecture from each period. Unlike Taipei—where many important districts and public buildings were rebuilt in traditional Chinese or modernist styles to project a new regime’s image—Tainan’s lower development pressure and land values allowed many Japanese-era, Qing-dynasty, and even earlier structures to survive.

Taiwan has both high-speed rail and metro systems. The HSR is quite convenient—Taipei to Tainan takes only about 90 minutes, with trains every 15 minutes or so. It feels more like riding the subway; barely any queuing required.

Taxis in Taiwan are surprisingly expensive, nearly comparable to Vancouver (I later learned Vancouver is actually among the cheaper major cities in developed countries for taxis—thanks to the influx of Indian immigrants). Other prices are roughly on par with Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou.

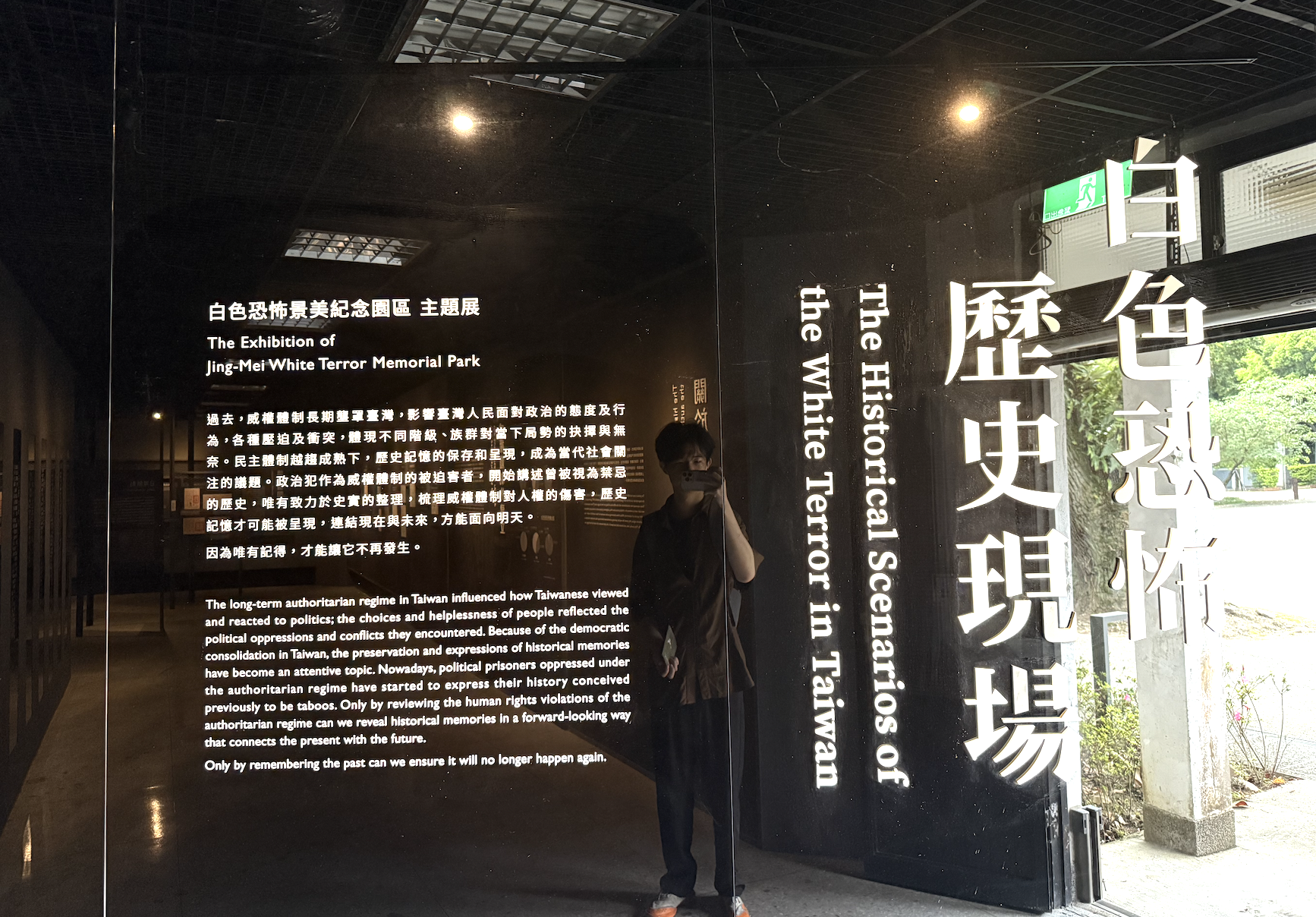

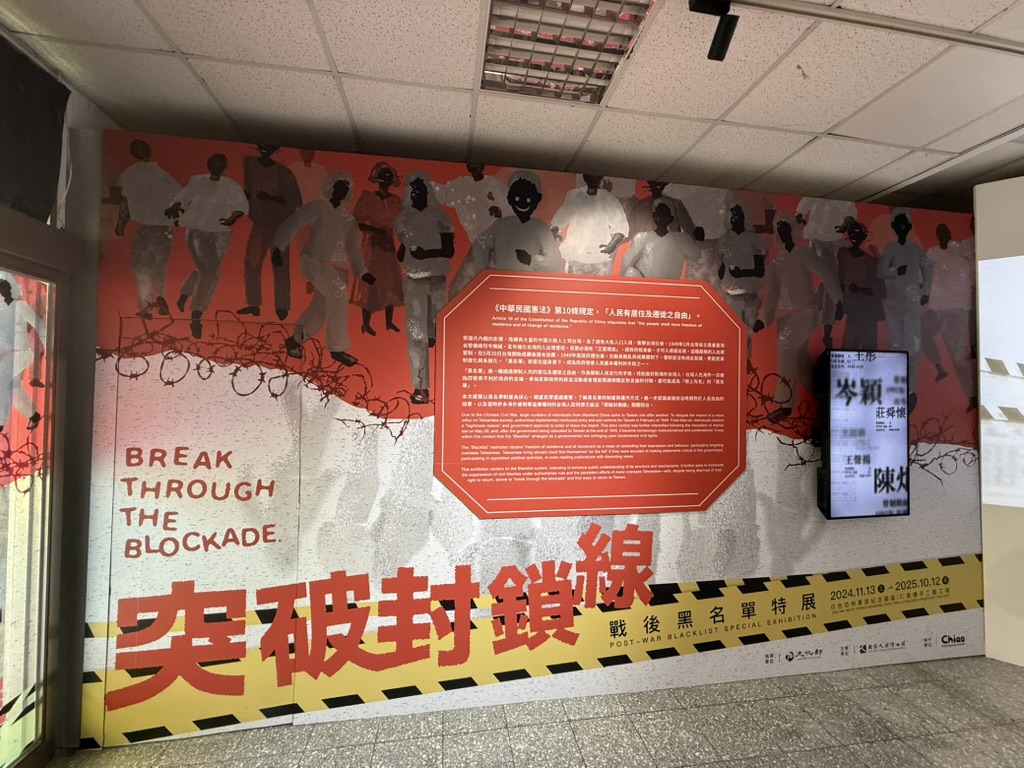

Over these days in Taiwan, I visited many political and historical sites and museums. The curation quality was excellent—nearly every exhibition held my attention and left a deep impression. Though admittedly, this might partly be because their collections are limited, forcing them to compensate with thoughtful presentation design. Many museums offer free admission and are staffed by numerous employees and elderly volunteers.

Unfortunately, my two days in Taipei fell on a weekend, so I couldn’t visit the KMT or DPP party headquarters (apparently the KMT is quite welcoming to visitors).

I could definitely sense that due to cross-strait developments in recent years, the overall narrative has been de-emphasizing the Republic of China period of modern history, instead highlighting Taiwan’s localization and democratization process.

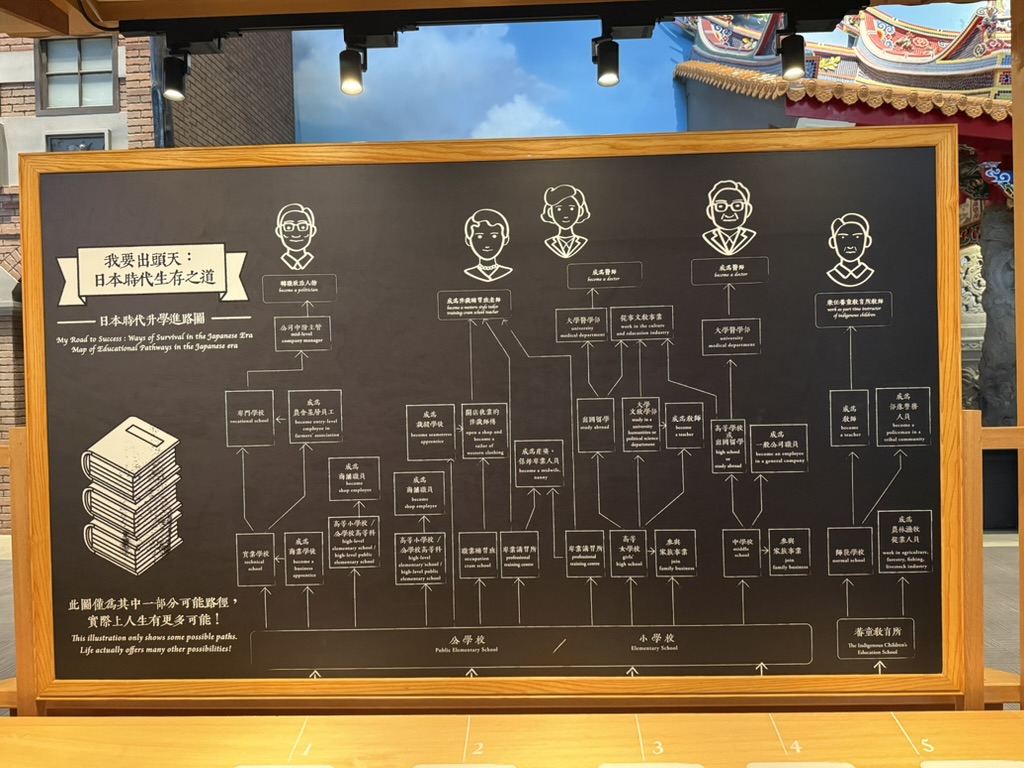

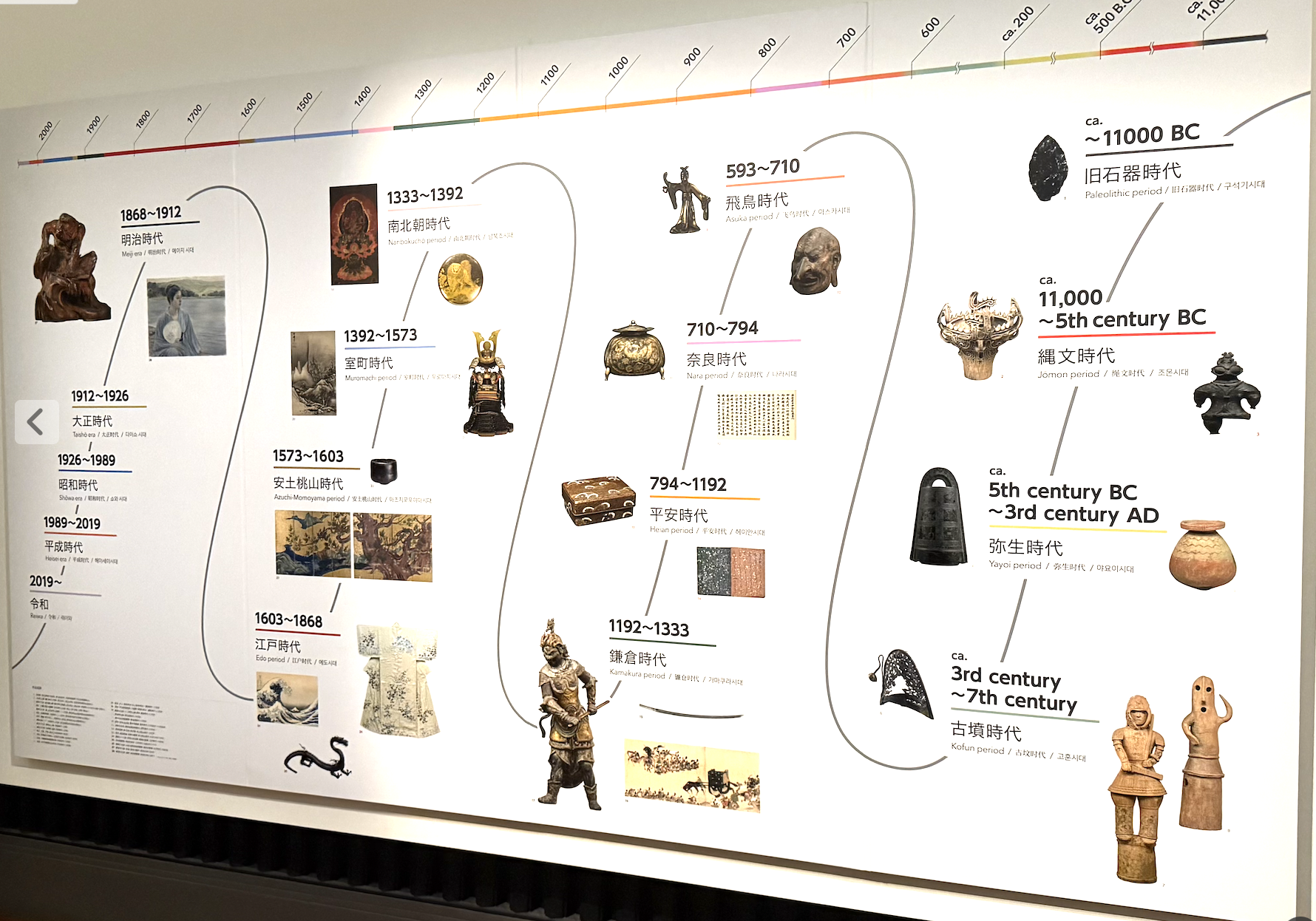

At the National Museum of Taiwan History (in Tainan), there were extensive displays about the Japanese colonial period—far more photos and artifacts than I’ve seen in museums in Japan itself (in fact, Japanese museums seem to actively avoid displaying anything related to the modern era). The exhibits showed newspapers, propaganda materials, everyday items from that time, and captured the public’s conflicted attitudes toward Japanese rule.

I’ve heard Taiwan’s east and west coastlines rank among the top 3-5 most beautiful in the world, perfect for cycling or driving around the island. Unfortunately, I probably won’t get that chance. But I should return to Taiwan in the future to explore the eastern side and places like Green Island.

🇯🇵 Tokyo, Kyoto & Osaka

After leaving Taipei, I met up with friends in Tokyo. I thought traveling before China’s May Day holiday and Japan’s Golden Week would mean fewer crowds, but there were still tourists everywhere.

I’d heard that rural Japan offers excellent travel experiences, but since this was my first visit, I mostly stuck to the metropolitan areas, hitting the famous spots—temples, shrines, and such. I basically did a whirlwind tour of the mainstream attractions across these three cities.

Honestly, I’m not particularly interested in most of Japan’s popular tourist sites at this stage. What really intrigues me about Japan is its history after the Meiji Restoration. However, due to America’s post-WWII demilitarization and ideological reformation of Japan, public exhibitions on this period are fairly obscure.

Japan’s public transportation is incredibly developed—dense subway networks, though stations are sprawling inside, meaning you often have to drag luggage for quite a distance. Taxis are also extremely expensive. This solidified my resolve to travel with just a backpack in the future.

Also, Japan really is like the anime and dramas portray working life—subways packed with salarymen, all in suits and ties, ranging from their twenties to their fifties or sixties.

I’ve seen plenty of North American programmers on social media lamenting and envying Japanese life, which made me curious. Personally, I feel Japanese and North American lifestyles sit at opposite ends of the individualism-collectivism spectrum—vastly different. Though if you’re working for a foreign company in Japan, or living there as a foreigner, the experience is probably pretty great across the board.

From street corners to tourist sites, you can feel Japan’s thick atmosphere of consumerism—stronger than many Western countries. Perhaps it’s cultural—in the West, values around freedom and individualism lead some people to resist or downplay consumerism, while in Japan, collectivism and social etiquette make people more naturally embrace this consumption rhythm.

On my last day, I walked into Yūshūkan —a military museum next to a certain shrine—with a critical mindset. The exhibits genuinely floored me. Many modern wars are described as “ordinary conflicts between nations,” with aggression and oppression cleverly obscured or even beautified. This narrative contrasts starkly with the historical facts we know, and gave me a visceral sense of revisionism existing in physical space.

After the war, America thoroughly transformed Japan: dismantling militarism, diminishing the emperor’s sacred status, implementing a peace constitution, gradually steering Japan toward modern democracy and a peaceful society. Objectively speaking, MacArthur’s reforms were extraordinarily successful, not only changing Japan’s political system but profoundly reshaping social values and the education system. West Germany’s experience was similar, which led America to briefly believe during the Cold War that this “democratization transformation” model could be replicated elsewhere.

However, facts have shown this kind of transition can’t be achieved through simple institutional transplantation. America has attempted this in Latin America, the Middle East, and Eastern Europe multiple times, mostly ending in failure or turmoil.

Mainstream Japanese education and academia have acknowledged and accepted war responsibility, yet spaces like Yūshūkan still exist, providing a stage for alternative narratives. Walking through the exhibition halls, you can clearly sense a selective memory at work: emphasizing Japanese sacrifice and suffering while deliberately avoiding aggression and oppression against Asian neighbors. This isn’t an oversight—it’s intentional historical reconstruction, packaging “invasion” as “conflict” and disguising “perpetrators” as “victims.” In this narrative, Japan’s own trauma is magnified while the massive harm inflicted on others is nearly erased.

This naturally relates to Japan’s modern militaristic education system—extreme emperor-worship, collectivism, total state mobilization—which shaped a generation’s values of unconditional obedience. In this atmosphere, brutal warfare was rationalized, invasion and atrocities were dressed up as “justice” and “glory”—values that seem utterly unimaginable in today’s peaceful era, yet became social consensus at the time.

The enormous trauma it inflicted is deeply etched not only in China but extends throughout East and Southeast Asia, even affecting Japan itself (modern Asia was truly a land filled with suffering). Even today, these memories remain unavoidable shadows in regional relations.

For the Japanese right wing, the “invincible” empire that dominated Asia during WWII still represents glory. They struggle to face the reality of military defeat because thorough reflection would mean not only acknowledging the nation’s past crimes but also touching the foundation of national identity. Thus, exhibitions like Yūshūkan become a form of psychological compensation—rewriting history to transform defeat into another kind of “honor.”